Research by scientists of the EU-funded DIGYMATEX project has demonstrated a link between digital maturity and successful regulation of aggressive impulses, opening up new possible methods for successfully intervening and boosting more responsible online behaviour, among both youth and adults.

The study, titled “Developmental structure of digital maturity” and published for Computers in Human Behavior’s August 2024 issue (made available online on April 11), was carried out by Lieke Hofmans and Annemarijn van der Stappen of the University of Amsterdam’s Department of Developmental Psychology and Wouter van den Bos of the University of Amsterdam and the Max Planck Institute for Human Development’s Centre for Adaptive Rationality in Berlin.

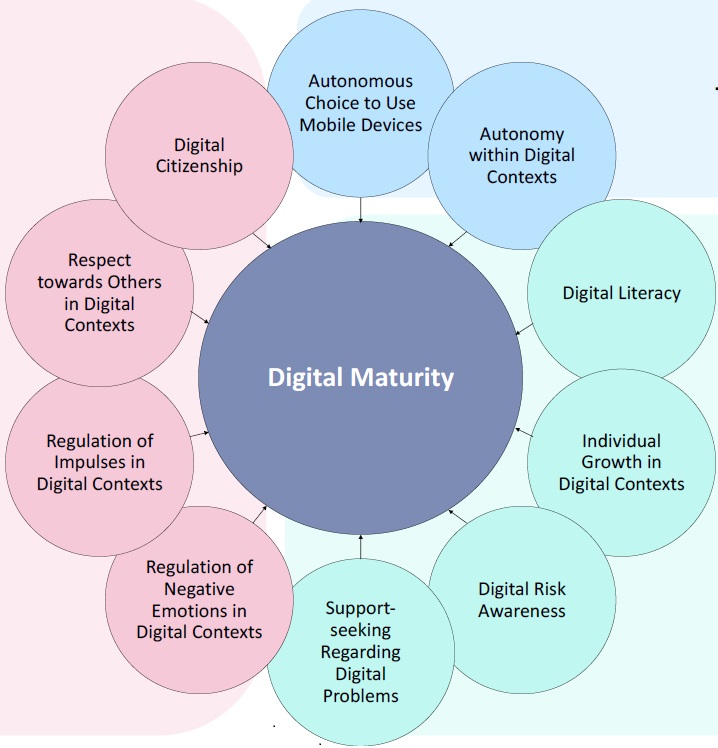

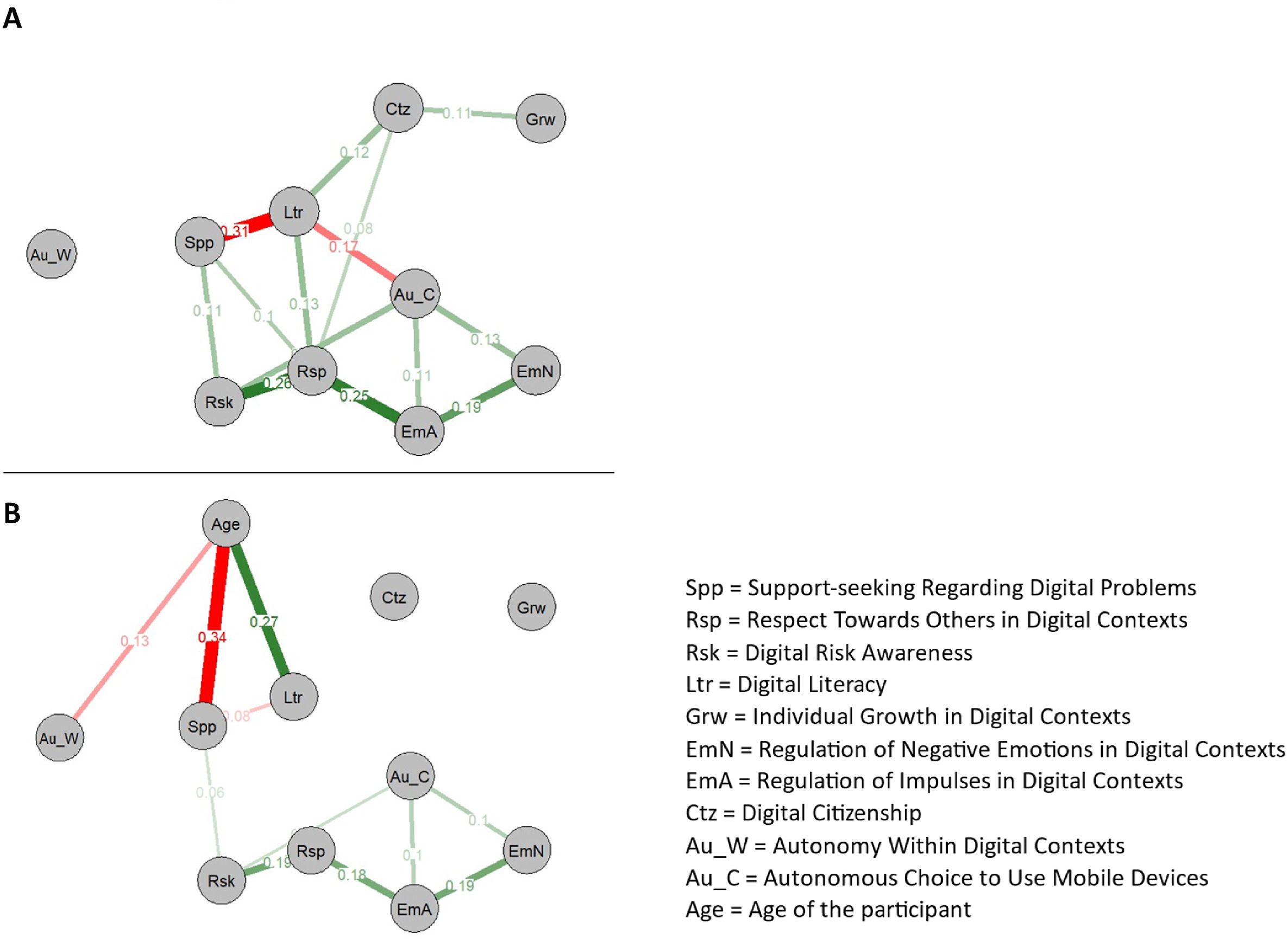

The researchers used a moderated psychometric network modelling approach to examine how the ten dimensions of digital maturity, as specified in the DIGYMATEX Digital Maturity Index (DIMI) interact and their relative contributions to digital maturity as a whole. The ten dimensions of digital maturity are defined as: autonomous choice to use mobile devices, autonomy within digital contexts, digital literacy, individual growth, digital risk awareness, support-seeking regarding digital problems, regulation of negative emotions, regulation of impulses, respect towards others in digital contexts and digital citizenship.

“What we found was that support-seeking and regulation of aggressive impulses played a relatively central role in the network,” said Lieke Hofmans. “These skills are thus potential targets for interventions to improve digital maturity, although future intervention studies would have to confirm this. For example, already developed interventions for reducing aggressive impulse regulation have shown to be promising in offline settings, and could therefore be translated for the online environment to result in more considerate behaviour and decision-making,” she suggested.

Hofmans noted that the study’s primary aim was to identify which of the ten DIMI dimensions play the strongest roles in determining overall digital maturity, as assessed by the robustness of their relationships with other dimensions. The dimensions identified in this way would then be revealed to be the “focus domains” which, when bolstered, would have a “particularly beneficial effect” on the other dimensions and therefore reinforcing and increasing individuals’ digital maturity as a whole.

A secondary aim of the study was to assess whether the network structure underlying digital maturity differs between age groups. No interaction of the network structure was found with age among their respondents, who ranged in age from 9 to 43 years old, the researchers said, calling it a “striking conclusion”. The same elements were therefore shown to underpin digital maturity for children, adolescents and adults.

“This suggests that the interrelationships within digital maturity are largely robust and potential interventions can be similar for different age groups,” Hofmans commented.

Although age was not demonstrated to be a factor moderating connections within the network, the study did find that older participants were more digitally literate and asked less often for support regarding digital issues.

Future research could extend the respondent sample to include populations from a wider range of various cultures would potentially bring new, interesting insights, Hofmans suggested. The sample for the study published was composed of 378 participants living in the Netherlands and Germany, whose digital maturity was measured through their answers on a questionnaire.

“It is of course conceivable that other cultural groups exhibit different dynamics within digital maturity,” Hofmans said.

Another area for future investigation could focus on developing Digital Citizenship, one of the ten dimensions on which participants scored relatively low. “However, interest in youth online civic engagement is increasing, and educating teens on how to use the online environment and social media for civic participation could prove fruitful,” the researchers noted.

Recent decades have seen increasing concern regarding the negative effects of digital technology on adolescents’ wellbeing, alongside recognition of positive effects and the desire to balance the two.

Individuals vary largely in their susceptibility to the negative effects and ability to take advantage of the positive effects, owing most likely to individual differences in the way people interact with digital devices and manage their online behaviour, the researchers noted.

“Digital maturity aims to capture the extent to which young individuals use digital technology in a healthy and adaptive way”, they summarised.

“Interestingly, making thoughtful decisions about the specific content to engage in was rather unconnected within the network, suggesting that choosing the specific online activity is less decisive for digital maturity than choosing whether to go online in the first place,” the researchers said.